China remembers Canadian doctor Norman Bethune

|

|

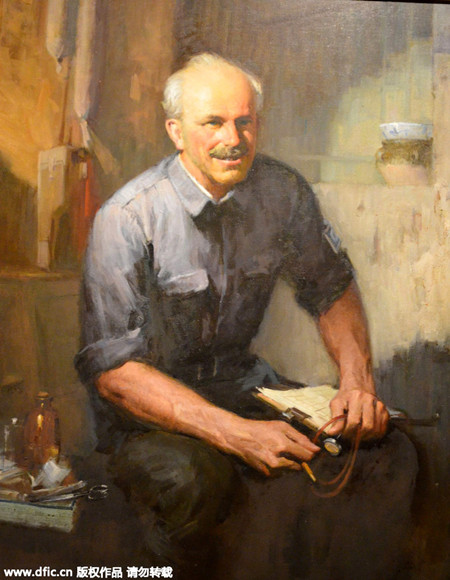

An oil painting of Canadian doctor Norman Bethune at the National Museum of China in Beijing, Aug 28, 2015. [Photo/IC] |

One of the most honored foreigners in the history of the People's Republic of China is an Ontario-born doctor little-known to the Western world outside Canada.

Norman Bethune is revered in China for the humanitarian service he rendered during the early years of the invasion Chinese call the War of Resistance against Japanese Aggression. The 1937-1945 war spanned the conflicts that the rest of the world calls the Second Sino-Japanese War and World War II.

A small crowd gathered at The Bookworm bookstore in Beijing on Sunday to learn more about the doctor, who died bringing wartime medical care to soldiers and the poor.

"He was praised as the perfect role model to follow," said Yan Li, director of the Confucius Institute at the University of Waterloo in Canada.

Li, who discovered the only known photo of Bethune with Mao Zedong, was one of three speakers. Bill Smith, whose parents were close friends of Bethune, and Norman Bock, whose novel about Bethune, The Communist's Daughter, also spoke.

Smith said Bethune was an early proponent of socialized medicine and a daring doctor whose innovative technique in treating tuberculosis - temporarily collapsing a lung so it can heal - saved the life of his mother, Lilian.

Bethune, a World War I veteran and anti-Fascist who was a member of the Communist Party of Canada, came to China in early 1938 to serve in a war-ravaged country desperate for medical help. He had attracted international attention during the Spanish Civil War, where he developed a method for transporting blood for transfusions.

While he was serving with China's renowned Eighth Route Army, Bethune brought modern medical care to rural poor people as well as wounded soldiers, which earned him enduring gratitude in China. The doctor fell mortally ill to infection after cutting his finger during surgery and died from septicemia in November 1939 - less than two years after arriving in China. He was 49.

His loss was deeply felt and his memory preserved in China decades after the end of the war. Chinese who attended school in the 1960s were required to read and memorize parts of Chairman Mao Zedong's eulogy, In Memory of Norman Bethune.

Statues have been raised to his memory and the highest medical honor in China is the Norman Bethune Medal.