|

|

Ma Xuejing / China Daily |

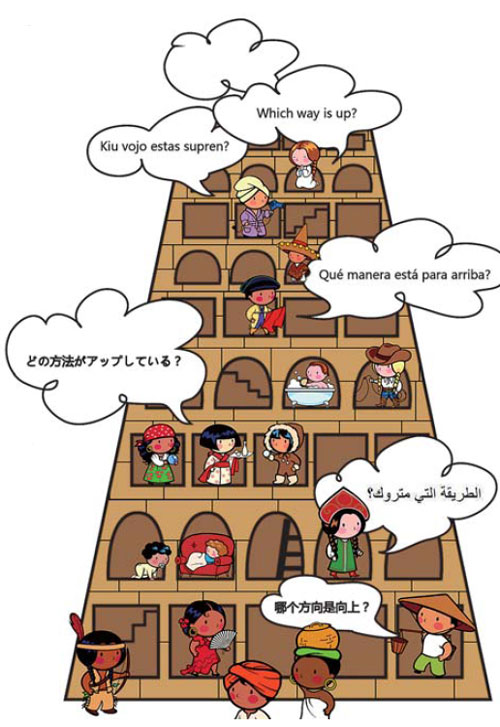

China's opening-up in the 1980s created an instant demand for translators as the nation reached out to the world. Thanks to nonstop economic growth, people-to-people exchanges and Chinese aid to other nations, speaking in tongues is a ticket to the future, Mike Peters reports.

Most often, a bad translation is just funny. Whole books have been compiled about "Chinglish" signs. But sometimes a fumbled rendering of language can be offensive.

Or even fatal.

Take, for example, a European winemaker and animal lover who has taken in abandoned cats, dogs and even a donkey during his years in China. One night he became nearly distraught when he realized that, in the restaurant where he was dining, dozens of pigeons were being hauled from coop to cookpot just a few meters away while folks like himself placed their dinner orders.

After a brief internal struggle, he could stand it no longer. He summoned the manager and declared he would buy every bird the manager had to take home.

"All of them?" the manager asked through an interpreter.

Then the delighted restaurateur went out back and began wringing feathered necks left and right, as the kitchen went into high gear to prepare the giant takeaway order.

Everybody has a funny story about interpreting gone wrong, but converting words from one language to another is serious business - one that has been booming on several levels since China's opening-up began in earnest in the 1980s.

It can make you a star, from inside the establishment or far outside.

Lin Chaolun, a native of Fujian province, is known for translating for Britain's Queen Elizabeth II and former prime minister Tony Blair. A graduate of

More famous, or perhaps infamous, is Su Feifei. Her translations of adult video games from Japan have been an Internet sensation in China - and earned her a short stint in prison. Her website 3DM, with a forum run by some paid but mostly volunteer translators, has fans from players to pirates to social commentators.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|