When the tea bowl met the tea stand

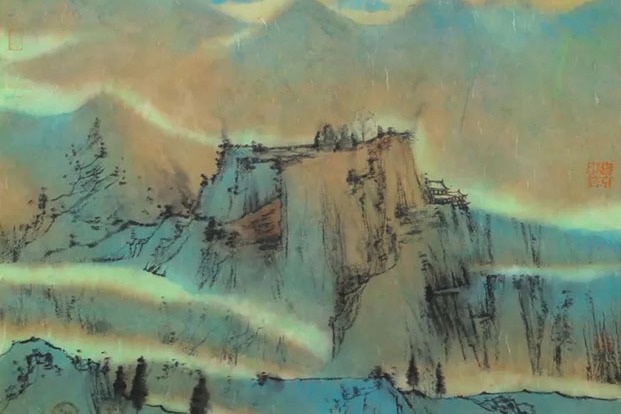

One of them is by Shitao (1642-1708), who employed thin lines in faint color in his depiction of mountainous caves, from which these reclusive men would emerge.

Shitao, whose original name was Zhu Ruoji, was born into the ruling Zhu family one year before the fall of the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644). Taken into hiding in a temple as a toddler as the rest of his family was massacred by the new regime, Shitao later spent many years in the temple, all the while finding it hard to forsake his longing for fame.

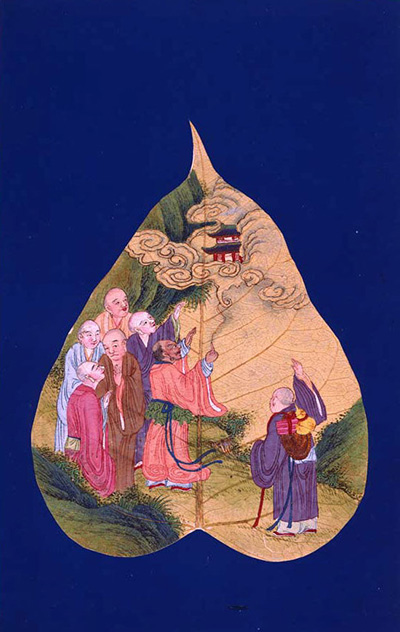

In his painting, one of the Luohans is pouring water from a thinnecked bottle. The stream runs off toward the end of the scroll, where it morphs into a dragon, the ultimate symbol of supernatural and regal power throughout Chinese history.

A more grotesque rendering of the Luohans was given by the Ming Dynasty painter Wu Bin, who lived a century earlier. With bulging forehead, slightly contorted face, the occasional side whiskers or bushy beard, and most notably, long curved fingernails more likely in Western folklore to be associated with a witch, Wu's Luohans are combinations of a tough hide and a tender heart.

"Keeping in mind that Buddhism first originated in India, such depiction reflects the Chinese imagination of people from West Asia and the Indian subcontinent," Scheier-Dolberg said.