Planet's oldest footprints offer brand-new mystery to science

Here's one set of footprints that's going to be hard to track.

Some critters - about a millimeter long (that's about four one-hundredths of an inch) - were crawling and burrowing through a patch of shoreline mud in what is today China about 550 million years ago.

Scientists are suggesting that these trails - dubbed the Shibantan trackways - could very well be the oldest footprints on Earth. But what made them is the big mystery.

Thanks to the process of the mud being transformed into limestone stone,the two miniscule rows of tracks made by the creature(s)unknown were preserved for eons in the Yangtze Gorges of southern China. Dating the rock by the strata it was taken from puts it in the Ediacaran period, between 541 million and 551 million years ago, an epoch that so far has offered up a scant fossil record of mostly worms and tiny sack-like organisms.

No evidence of creatures with legs this old has ever been discovered. All previously identified animals with paired appendages were from the Cambrian period (530-540 million years ago), a time that witnessed an outburst of different and more complex forms of life. That era's crawlers left trails and tracks all over the place.

Professor Shuhai Xiao, a geobiologist at Virginia Tech and author of the paper that appears in the current issue of Science Advances, told the Guardian that the discovery sheds light on what creatures were the first to evolve pairs of legs, which, of course, would eventually enable them to crawl onto dry land.

"Animals use their appendages to move around, to build their homes, to fight, to feed, and sometimes to help mate," he said. "It is important to know when the first appendages appeared, and in what animals, because this can tell us when and how animals began to change to the Earth in a particular way."

The stride and locomotion of the two sets of tracks are difficult to puzzle out. Asymmetrical, irregular and overlapping, they almost suggest a gait that might be called staggering. The irregularity is in marked contrast to the "highly coordinated" wave-like rhythmic motion of other insects, Xiao explaied.

"The footprints are organized in two parallel rows, as expected if they were made by animals with paired appendages," Xiao writes. "Also they are organized in repeated groups, as expected if the animal had multiple paired appendages."

So what is it? The identity of what made the tracks, Xiao said, "is difficult to determine in the absence of body remains at the end of the trackways."

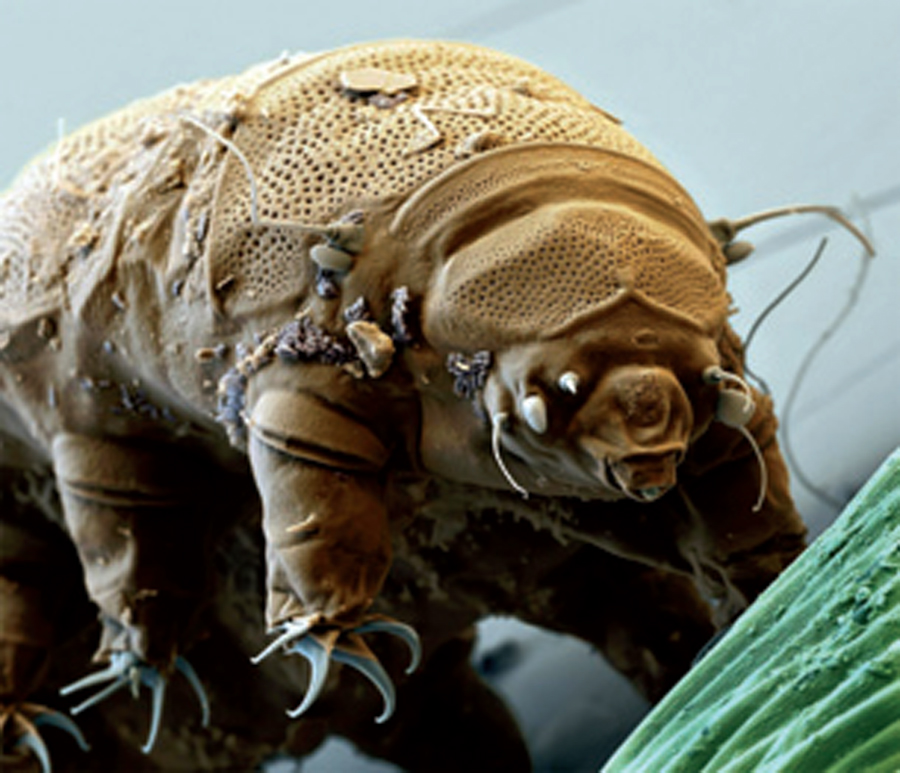

The style of movement points to arthropod (spider, crab, bug) with jointed limbs, but, Xiao writes, adding to the mystery, "it is not beyond the realm of possibility that theShibantan trackways may have been made by other animals analogous to modern annelids (worms), onychophorans (multi-legged worms), or tardigrades (A.K.A. water bears or moss piglets)".

It might also have been a tetrapod (the four-limbed phylum that includes humans).

My money's on the tardigrades "water bears", which were first discovered by a German zoologist in 1773 and have since been found literally everywhere, from the depths of the oceans to towering mountain tops, from sweltering jungles to the Antarctic ice, in sand, moss and barnacles.

They are also one of nature's most resilient creatures, able to survive conditions that take most other living things out - extreme heat or cold, radiation, lack of air, food or water. They are barrel-shaped with four pairs of stubby legs equipped with "claws".And they are ancient, dating back to the Cambrian.

Maybe the most obvious hint is right under our nose - in its names. The German biologist Johann Goeze first named the creature klinerWasserbaer(little water bear), because of its lumbering gait. The Latin name tardigrade came from an Italian scientist years later. It means "slow walker."